Welcome to Hallam Street !

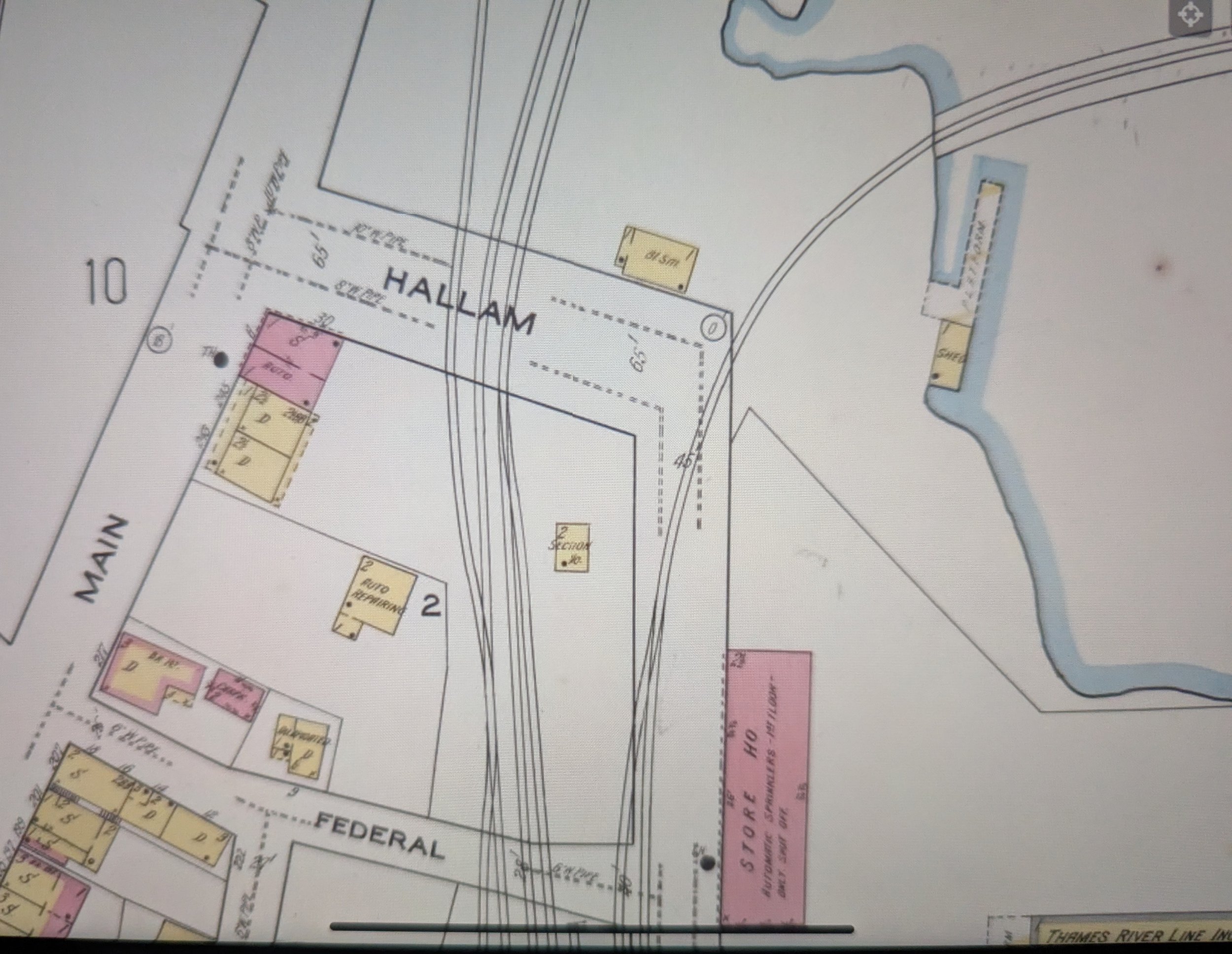

Inset of 1954 Sanborn Fire Insurance map, courtesy Library of Congress. Main Street is running north and south in the middle.

The following is an unpublished article submitted by the author to The Shoreliner magazine of the New Haven Railroad Historical and Technical Association in June of 2025:

There are parallels between the demise of New London‘s Main Street neighborhoods and the slow, lurching last decade of the New Haven Railroad. The focus in this article is the Hallam Street railroad crossing and its immediate neighbors over the course of history, ending on December 31, 1968, the final day of operations for the New Haven road.

Colonial New London, enter the Hallams

By American standards, New London, Connecticut is an old city, incorporated in 1646, under the direction of John Winthrop, later to become the first colonial-era governor of the state. As a port on the eastern edge of Long Island Sound, the settlement had a protected harbor and would soon grow with trade in the West Indies, notably Barbados and Nevis in the Caribbean. Horses, tools, and other iron goods went south, molasses, rum, and African slaves came north. Slavery would remain legal in Connecticut until 1848.

It is from Barbados, that in 1676, Captain John Liveen and second wife Alice Hallam with her two sons (by another marriage) arrived in New London. Both teenaged sons grew to be merchant seamen. The Hallams would eventually own the land south of the highway that ran from Towne (Main) Street to the town wharf or landing.

The highway was wide, being, until 1733, the only public access to the landing. On March 6, 1743, an event akin to a religious tent revival took place on that cold and windy Sunday morning. Mr. Davenport and his flock had the street by the wharf to themselves as no ferry to Groton was sailing at that time. According to Trumbull‘s History of Connecticut (1792):

Davenport preached a very impetuous exclamatory sermon to a gathering of Separates in front of the town wharf where he advised his hearers to burn all their idols, whether books, garments or jewelry and so vehement was his admonition and so great was his power over the multitude that they rushed to their homes, secured their idols, and under cover of night repaired to the open space near the town wharf, kindled a fire and cast into flames what they had brought for sacrifice.

As the Separates burned their books, it was reported that they daid these words:

If the author of this book died in the same sentiments and faith in which he wrote it, as the smoke of this pile ascends so the smoke of his torment will ascend forever and ever. Hallelujah Amen.

Interesting that the people were prevented from burning their clothes and jewels. Again, according to Trumbull‘s…

John Lee of Lyme told them that his jewels were his wife and children and that he could not burn them as it would be contrary to the laws of God and man, that it was impossible to destroy idolatry without a change of heart and their affections.

Below is the Hallam Street area shown in a 1761 map now hanging in the first floor lobby of City Hall. Towne or Main Street is running north and south on the left side, Hallam Street, then the Highway to the Ferry, runs east and west to the landing. The Hallam Store and Sun Tavern stand below. The Custom House stands above. Beach Street, now Water, runs parallel to the shore.

In 1761, grandson and Yale College grad Amos Hallam ran the Sign of the Sun tavern directly across from the town wharf. As an omen of good luck, the sun was sometimes used in naming a new business to insure good fortune, here the luck being to draw in gentlemen travelers thirsty for rum and entertainment. When Amos passed a couple of years later, his wife Sara sold the house to Zebulah Elliot who continued running the business as Elliot‘s Tavern. Over the next 18 years maritime commerce along the Beach flourished and the tavern on the corner did as well.

Fire returned to play the main role in British retribution on September 6, 1781. New London had become a significant port, and ss such, a haven for pro-independence privateers harassing vessels of the Crown.

General Arnold led his men on horseback down Towne Street coming south putting buildings to the torch on the water side of the street. At Hallam Street, the redcoat column turned left, marched a short distance further and halted at the town wharf. To the south along the Beach stood Arnold‘s objective: the stores, workshops and warehouses that had, from his information, been supporting the privateers. The general pointed his sword in their direction.

Soldiers, do your duty.

The Elliots had evacuated and perhaps watched from a ditance as their home and business burned brightly in the night, as the soldiers worked their way down the empty street. In less than three years however, the incinerated trade and commerce would be rebuilt and grow until the next tour de force marched through… the iron horse.

enter the railroads

According to Frances Manwaring Caulkin‘s History of New London (1860), the rail line from nearby Winthrop‘s Neck to Palmer, Massachusetts via Norwich, Willimantic and Stafford Springs was completed in 1850. Two years later the line from New Haven to New London was completed, skirting, as Miss Caulkins confirms, the picturesque Connecticut shoreline. A rail link through the city connected the two railroads and by late 1852 it was possible to travel by train from New York to Boston via Palmer.

A passenger station had been built by the early New London Northern at the northeast corner of Main and Hallam Streets. The Groton-bound ferries had stopped calling at the town wharf in 1793. They followed the path of commerce and investment south to the foot of State Street, where a larger slip was built near the future Union Station. (1887)

By late 1858, the Shore Line Railroad completed the 11-mile stretch from Stonington to Groton . With a ferry crossing the Thames River, it was now possible to continue on the shoreline route by rail to Providence.

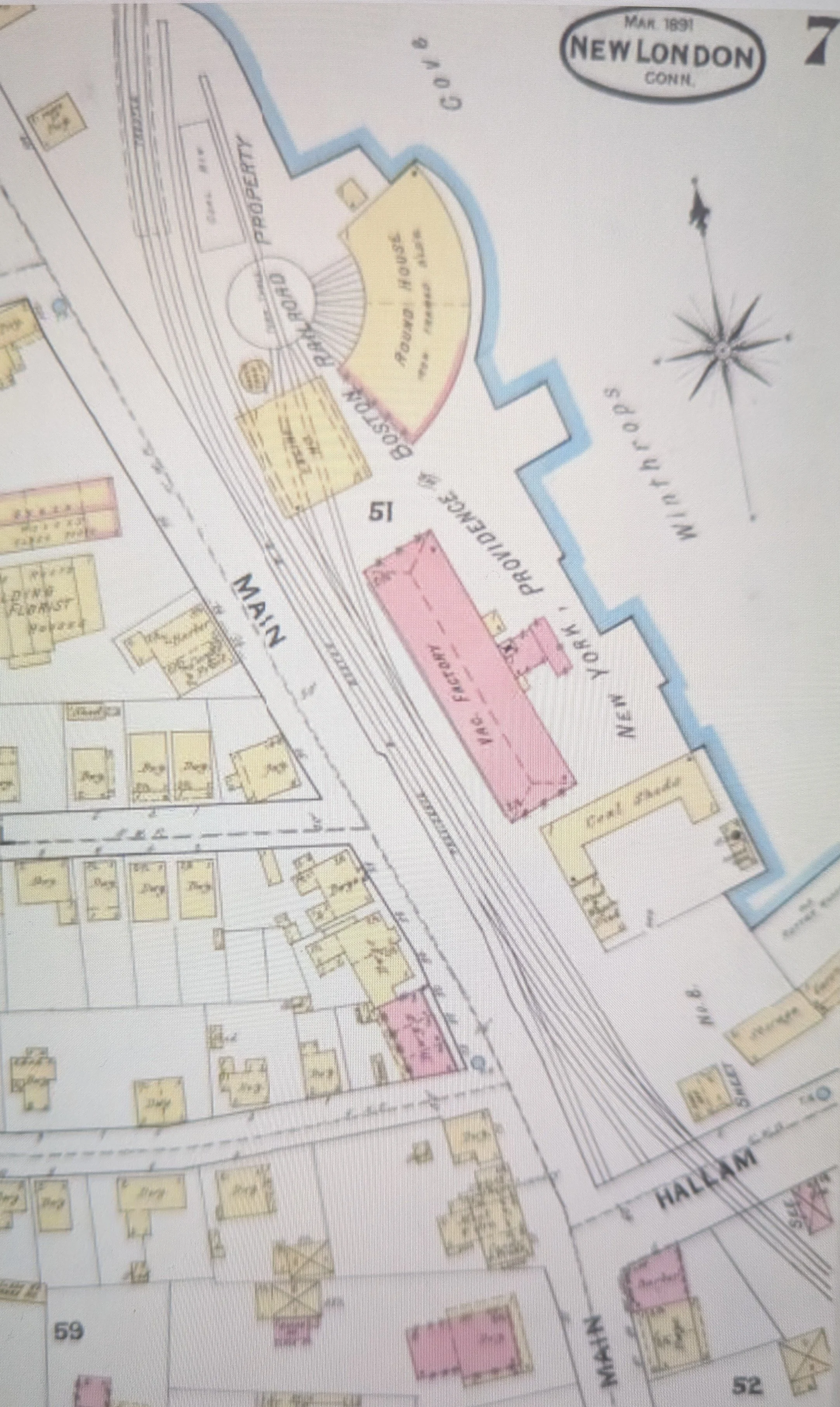

In this 1876 picture map the Shoreline Railway connects with the New London Northern at Hallam Street. Boston-bound passengers then crossed lower Winthrop Cove via a swing bridge and headed north to Palmer. courtesy Library of Congress

In 1889 shore line service to Boston went all-rail with the completion of the Thames River drawbridge. On the curved bridge approach just above Hallam Street, the New York, Providence & Boston Railroad built a small yard and roundhouse. In 1892, the New York, New Haven and Hartford (the New Haven) took over operations. The Whaling City had become a rail hub.

Sanborn fire insurance map, 1901. courtesy Library of Congress.

the New Haven road

In 1905, Hallam Street Yard and roundhouse started to lose importance as the New Haven completed a large hub at Midway in Groton. The roundhouse lost its purpose as engines and their servicing went to Midway. A local demolition contractor took the landmark down in 1908, selling the structure‘s cast iron for scrap.

Sanborn Fire Insurance map, 1891. Courtesy Library of Congress

Hallam Street Yard remained for awhile and in the final years contributed to the New Haven‘s last profits. Hoppers of roadbase stone rolled into the yard to be loaded on trucks for site work on what would soon become New London‘s share of Interstate 95 in 1961. Of the three remaining tracks one was used as a team track for local deliveries. Rolls of paper or newsprint for The Day arrived in Bangor & Aroostook boxcars sporting the large BAR markings. Heavy equipment arrived on flatcars. One such load, a crane ordered by a Groton firm, caused quite a stir on the morning of May 10, 1960. Non-railroad workers using a torch to cut cables securing the crane set the creosote timbered loading platform on fire. Incredibly, there was no hydrant nearby and a hose had to be run in from Main Street. Oil drums on the platform ignited. The black and gray billows were seen for miles. In the end, the fire burned out with the help of retardants leaving behind a ruined crane, flat car, and loading platform.

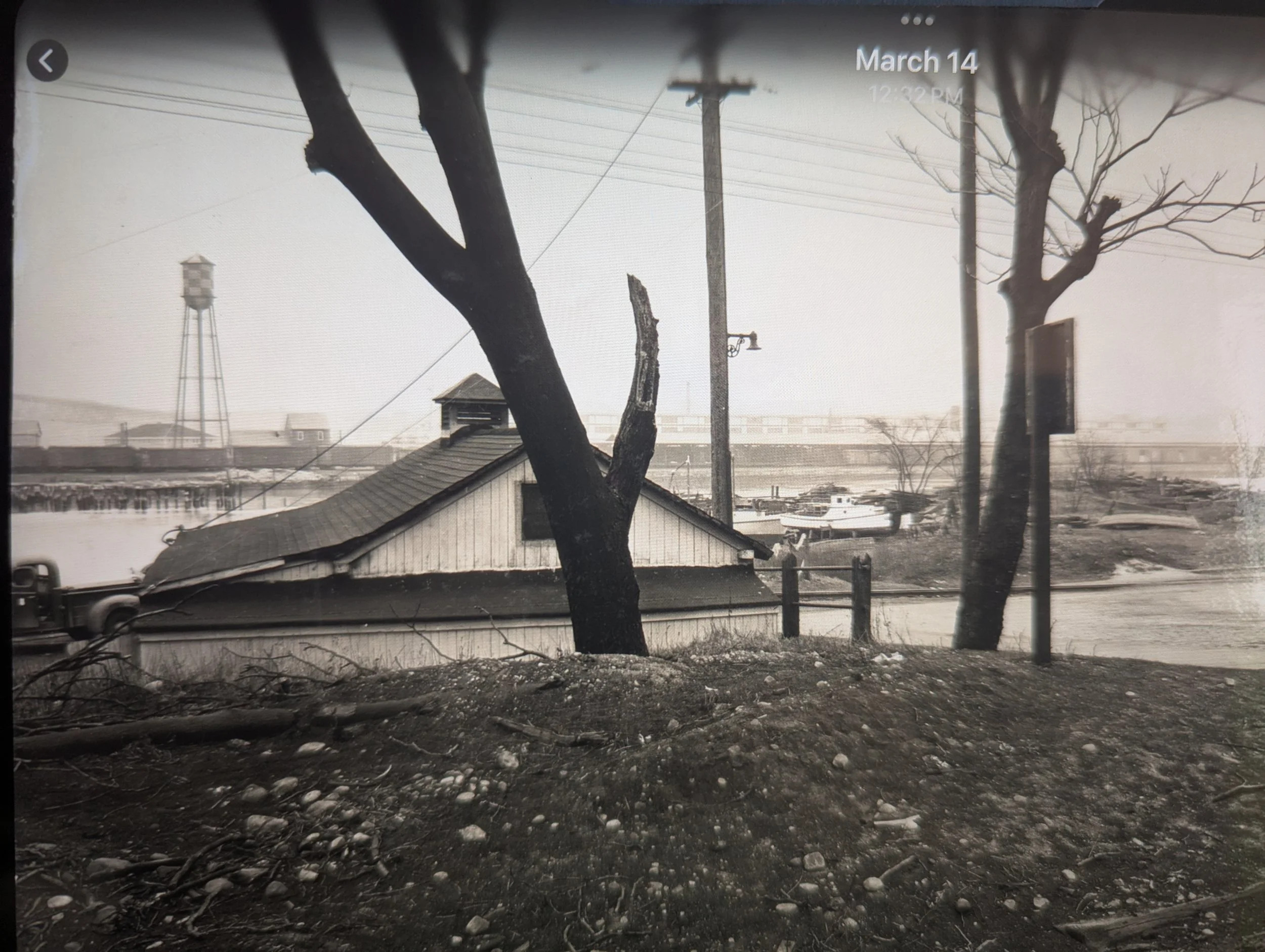

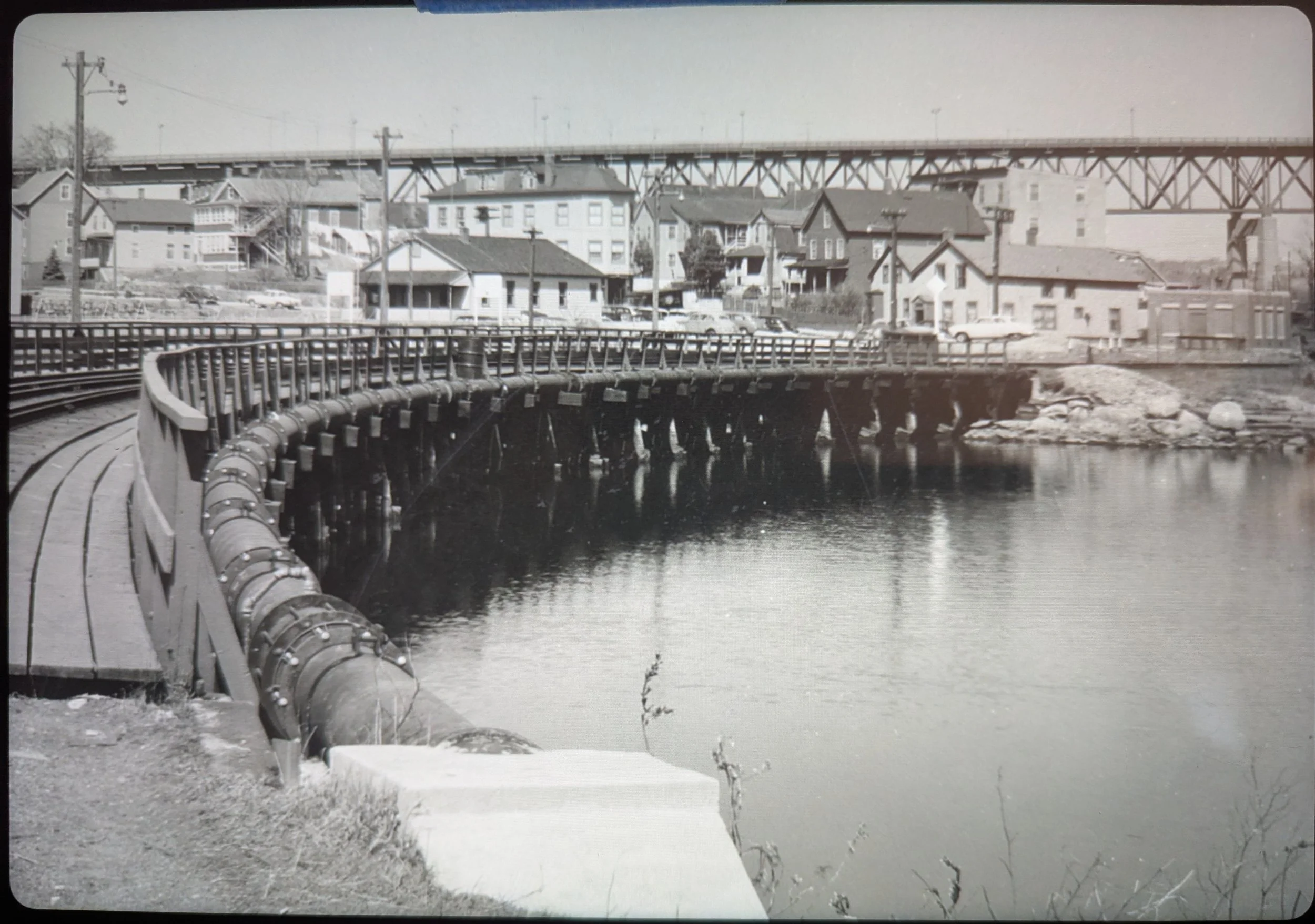

Photo below shows Winthrop Cove above the New Haven right-of-way (left), leading to the Thames River drawbridge. Hallam Street Yard on the right backed by apartment buildings lining the west side of Main Street. And yes, the motorboat in the foreground sold. Courtesy George Oldershaw, 1961.

The New Haven also used the yard as a maintenance of way facility with a burro crane, a few gondolas and flats, the mandatory NE-5 caboose and an Alco RS-1 road switcher. Occasionally a behemoth Pennylvania Railroad wreck crane would pay a visit to sort out mishaps caused by neglected track or rolling stock.

In the mid-sixties, the cash-strapped railroad sold the property to redevelopment. Today the space is Fulton Park named for the sub-tender #11, stationed at that time along the river side of State Pier. The basketball courts continue to see frequent use today.

The freight revenue from highway construction and property tax relief in all four states served by the New Haven were thought by many sufficient to keep the railroad running, the commuter, passenger, and freight trains rolling. They weren‘t. The railroad filed for bankruptcy on July 7, 1961.

This enlargement of the 1961 Oldershaw photo shows more clearly the west side Main Street building line up above the New Haven tracks and Hallam Street yard. Note the stone block retaining wall on the left, the widow‘s watch silouette of the B.P. Learned House at Federal, the 3-story brick Captain Stevens Rogers home at Shapley, the break between buildings (blue on left side, red/gray with single dormer on right) at Hill and the imposing Phillips House just above the orange New Haven caboose. Alas, the church steeple of the First Congregational Church is also gone, due to a structure defect never corrected and leading finally to the steeple collapse in 2024. Perhaps the hand of divine intervention prevented any injuries or loss of life,

view from the tower…

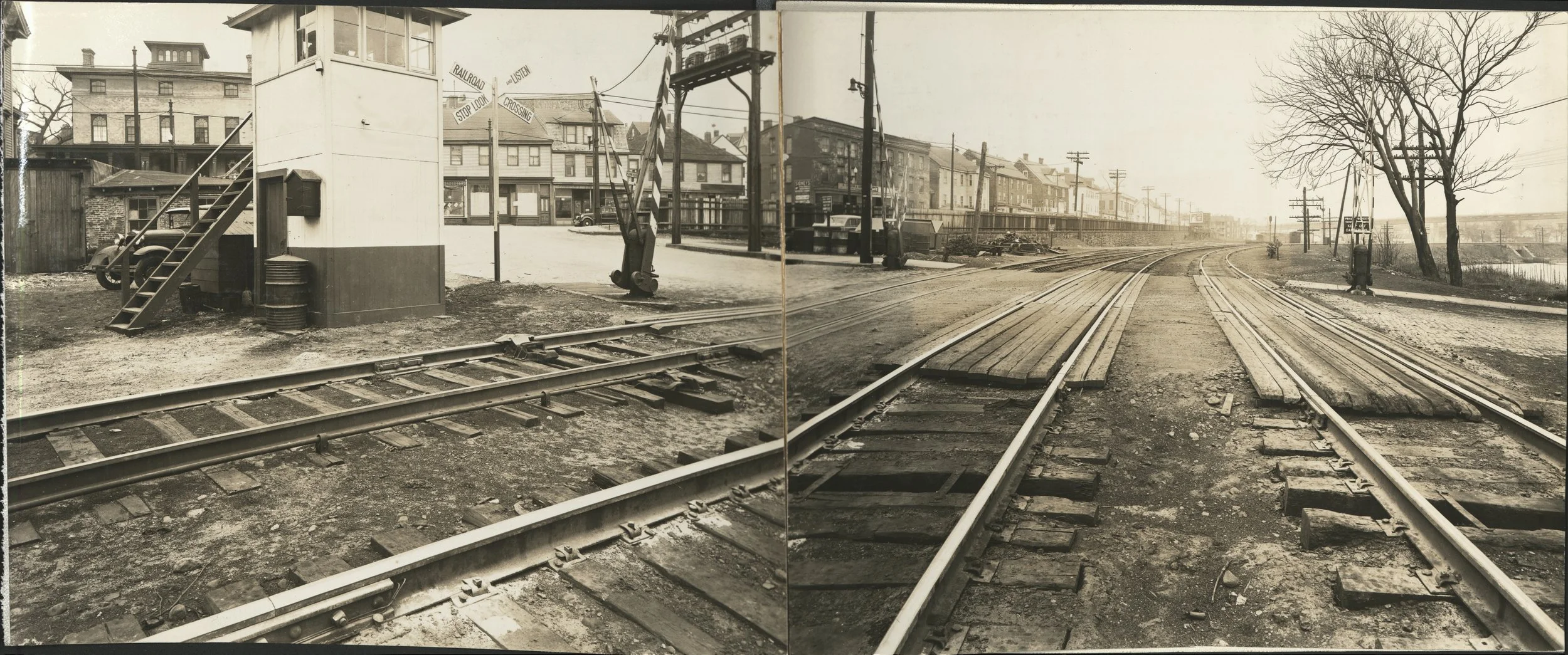

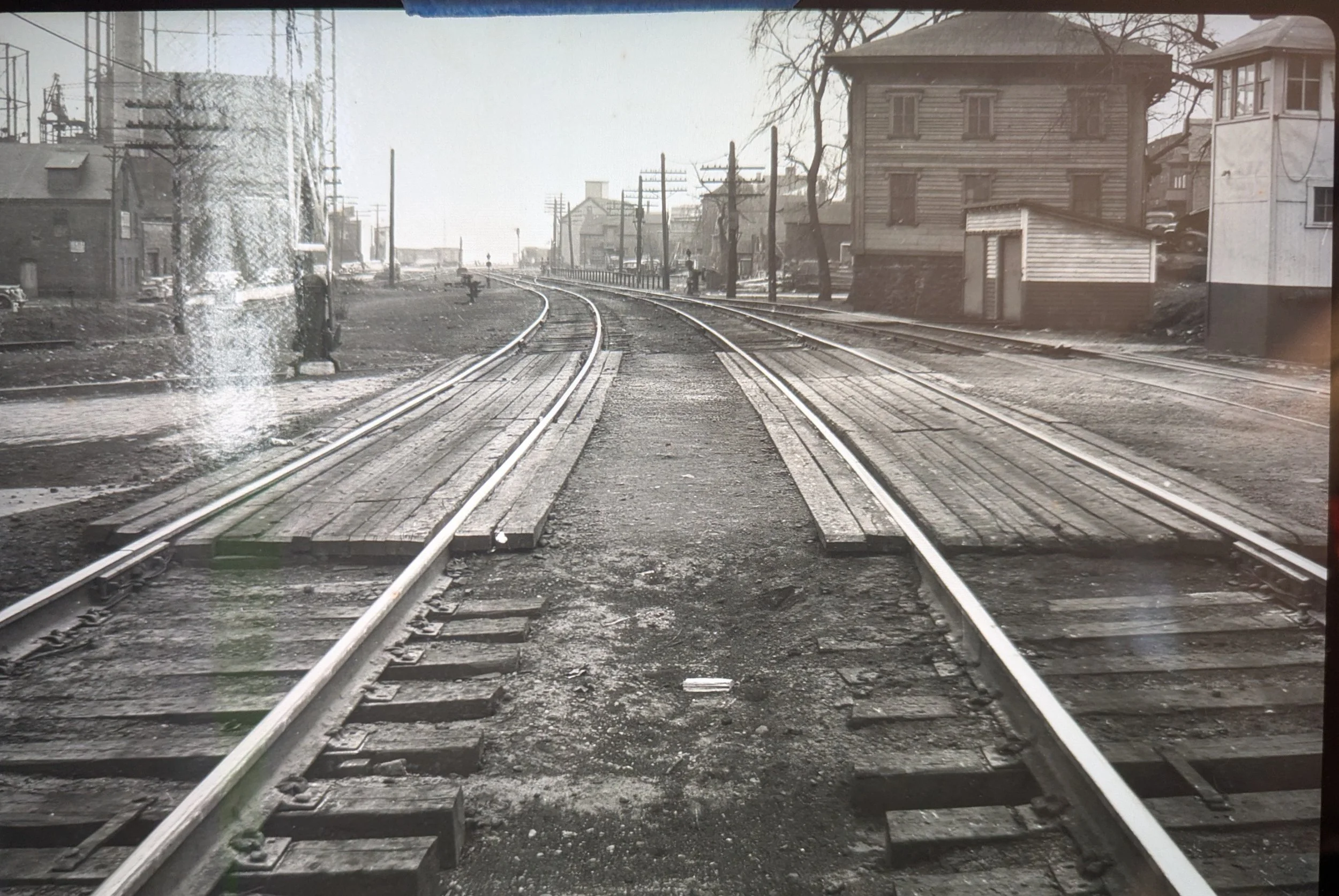

We are standing at the spot where Amos Hallam‘s Sun Tavern stood in 1761. It is now 1944… through the miracle of magnification and good resolution in the photograph we can ascertain the following: A. Gordon & Son package store (Yellow Front) is at the north corner of Main and Shapley, A. Heller Shoe Repair is at 274 Main, and 272 Main is vacant. Note the derail clamp on the far rail of the track leading to Hallam Street Yard. The parade of venerable buildings along the west side of Main seems to vanish in the fog. The villa just to the left of the crossing tower is the Miner Family (whaling) villa at 250 Main… the B.P. Learned House former Lawrence family villa, a near twin, at 230, is out of the picture. Photo courtesy the Peterson Collection, UCONN archives, Laura Smith, archivist

The crossing tower itself had a tender visible in the second floor window. Though normally a job for men, the New Haven did have a few female tenders such as Rachel Gates of Hartford. We learn more about her later.

Before the automatic crossing gates, warning lights and bells introduced in the late sixties, railroads employed crossing tenders who through an arrangement of levers, cables and piping, mechanically raised and lowered the black and white striped barriers you see in the picture. There were also red warning lights and a clanging bell to warn drivers and pedestrians. As we look at other crossing pictures from the same 1944 collection, you‘ll see just how central and well-trafficked a location this was at times.

The stately house on the left with laundry drying on the back porch is 243-45 Main Street. During the Depression, the Salvation Army used this as a hotel or industrial home. During this time period it most likely served as temporary housing for defense plant workers. More on this gem later.

If you look above the Coupe to the right of the tower you‘ll see part of the B.P. Learned House to the left of the Miner villa now used to accomodate the Visiting Nurses Association, Children‘s Aid, Workers Union, NL Day Nursery, and other charities.

Just left of center with the newspaper stand to the left of the entrance is Schuman Bros. Grocery, a business landmark throughout the thirties and first half of the forties. This building was the Reverend Woodbridge home built in 1769 and thus a survivor of Arnold‘s raid, but not redevelopment. The brick building looming over the house and its neighbors is the Sidney Manufacturing Company that made mattresses at the bottom of Shapley Street up until 1964.

These two villas I call the twins… the one on the left, 230 Main at Federal Street, is the Lawrence family villa, later to become the YWCA, later to become in 1925 or so, the B.P.Learned House with children and family settlement programs. The villa on the right, 250 Main Street, the former Miner family villa, later to become the home of associated charities such as the Visiting Nurses, Childrens‘ Aid, New London Day Nursery (day care), the Workers‘ Union and Girl Scouts. Both villas built about 1850. During the fifties the Miner villa was torn down, the property to be used as a playground by B.P. Learned. More on this later.

…and this spectral image, still in 1944, looks to the east… the blacksmith shop first appeared in the 1901 Sanborn fire insurance maps and remained standing til the late 1990s, oddly excluded from redevelopment only to succumb to Amtrak‘s electrification program and the closing of the Hallam Street closing in favor of a more practical crossing a bit further south in line with Gov. Winthrop Blvd. Note the checkerboard pattern on the State Pier water tank, red and white at the time, and the long string of boxcars, mainly used to carry grain from the mills further north in Franklin (above Norwich).

One more spectral image… the initial span of the Gold Star Memorial Bridge looms above East New London like a heavy curtain of fire-proof asbestos about to fall. Boxcars await on the the interchange track (left) with the New Haven Railroad. The carpentry shop sports a Central Vermont claim toward Dependable Freight Service through something called The Pioneer Westbound Differential Route which sounds like something I should have learned about in Mr. Allen‘s Geometry class. And, in case you missed him, there‘s a surveyor setting up his transit with a rodman waiting somewhere in the background. Shout-out to my father and all other chain carriers who machete‘d their way through the iron-tough, razor-sharp briars of eastern Connecticut.

We are still in 1944 at the Hallam Street crossing looking south toward Union Station which is out of picture on the right due to a track curve which follows the shore line. Follow the southbound track on the right. The tail of a passenger train can be seen making a stop on its way to New York or beyond. On the left side of the tracks is a tall , narrow structure just on the left side of the power pole standing closer to us.

This is the John Street crossing tower at Water Street. Thanks to The Day we know that the tender visible in the right-most window is William Storey and that he works the day shift as the caption states. Had he worked the night shift, Mr. Storey would have decorated the tower windows with lights. See the smokestack above the roof? Mr. Storey is keeping warm by the coal-fire stove. Photo credit to The Day, 12/22/69

Christmas is now three days away and we are in 1969. The Penn Central Transportation Co. now runs the New Haven as a regional part of a 21,000 mile system with a New Haven and a Boston Division. New London is in the Boston Division. Safety First ! (In six months time the Penn Central would follow suite and declare bankruptcy a mere nine years after the New Haven. The rail giant at one time was losing $17 a second.)

The straight, level right of way between the crossing towers at John and Hallam Streets proved a unique and at times very busy location where people, cars, trucks, and trains ran side by side, sometimes occupying nearly the same space. We‘ll pick up on two local practices that grew in popularity over the years, that is, from roughly 1910 to 1922 or so.

Imagine two railroads running long freights and passenger trains to multiple destinations… Boston, New York, Worcester, Montreal, etc. And just as when Interstate highways converge, there are traffic jams with trains, just like cars and trucks. Trains headed north toward the bridge also had to contend with a rising grade on long curve just past Hallam Street. As the freights were often long and heavy sometimes a train would stall. The engineer would then send a whistle signal to the conductor (remember there are no onboard radios at this time.) in the caboose that the train had stalled and that additional power was required, usually from Midway Yard in Poquonnock Bridge, Groton. A call would go to Midway from a trackside phone by the bridge. People living in the nearby streets came to recognize this signal and knew the train was temporarily stuck. During the fall and winter months these trains often had hopper cars in their consist laden with Pennsylvania coal bound for retail dealers and power plants. They often travelled at night due to daytime congestion with the busy passenger schedule.

Coal Harvesting

Thus, boys and parents from North Bank Street, Harrison Street and other nearby locations, climbed aboard the cars throwing chunks of coal down to children waiting with burlap bags. Coal burned cleaner, longer, and warmer than wood and in the cold water flats where heated wasn‘t provided, filching coal from the railroad seemed normal, a way of making ends meet. Families with no food in the pantry did have coal in the cellar. When Judge Coit asked 17-year-old Tinker Sullivan from the Great Eastern Coal Company occupying a vacant lot on Harrison Street (the young man’s company was housed in an office built of railroad ties, heated with an ash can stove, coal-fired of course) why his parents didn‘t pay for the coal he sold, his answer was simple: Well… where’s the money? Courtesy The Day, 1/31/1914

Two years earlier 12-year-old Henry Fulford was part of a group of boys taking coal from a train stopped just above Union Station. After the John Street crossing tender chased the boys away, some of the boys returned a short time later and stoned the crossing tower. The police arrested the boys. One of them was Henry.

Luckily, Truant Officer Thomas Ganey had taken an interest in the boy. No parents in the home, only a grandmother who seemed to work all the time. The court had placed Henry‘s sister in the state institutional school the year before. The boy, the officer discovered, had grown up on the streets with no adult supervision, with no adult care. Acting on Mr. Ganey‘s suggestion, the judge and prosecuting attorney agreed to have Henry placed on a farm where he‘d work and go to school. Henry thrived in the new environment to later graduate high school , run track, sing in a church chorus, perform with the Hackley Dramatic Club and serve on the local Negro Welfare Council. After retiring from the state highway department, Henry passed in 1970, the father of Henry Jr. Courtesy The Day, 3/1/1912

Boxcar Surfing

At some point, neighborhood boys (and some girls) noticed the swaying side-to-side motion of empty boxcars rolling at that magic speed between 7 and 11 m.p.h. passing slowly through town. Climbing the end ladders on a dare or some other form of encouragement, they reached the car roof and, standing in the middle with both feet planted firmly, arms extended, they became one with the swaying motion of the car, the wheels rolling atop the jointed rail, dipping as they beat down on the joints. Children called this boxcar surfing.

So how did this come to be?

Over the decades, The Day ran weekly columns written by an anonymous staff writer. News and editorial comment made up these short anecdotes that some might call musings or shortened trains of thought. Told by the Tattler was one of these columns. This particular edition came out on March 11, 1913 and explains better than I can the appeal of riding the rails as a playground game filled with thrills, companionship and daring. Let me digress from my narrative and give you a perspective from that time…

#######

Five small boys - none of them was what you would call a big boy - ran whooping along the roofs of a freight train crossing the Thames River bridge Sunday. They jumped from car to car in a death-defying game of follow-my-leader. In the street alongside the track a swarthy boy of 12 was playing baseball with some smaller lads. He had only one arm. I didn‘t ask him how his sleeve came to be empty. He was an East New London boy. I looked at the boys on the freight cars and the boy catching ball with one hand and I guessed. If I was wrong it was only once in a way. About once in so often an East New London boy is brought home to his parents minus one or more of his limbs - from the freight jumping game.

#######

The East New London boy doesn‘t steal perilous rides on railroad cars because he is differently constituted from other boys, but because he is brought up on a diet of railroads, so to speak, railroad tracks filling much of his horizon from the beginning of his toddlings out of doors. It is perfectly natural for him to make a playground of the trackage and playthings of moving locomotives (steam) and cars; and when he grows up to go to work on a railroad - if he survives the risks of his youthful adventures.

#######

Also it appears to be perfectly easy for him to follow his natural bent, so far as any interference from those in authority is concerned.

#######

It seems to me that the boys might be kept off the trains. If I had been a policeman, Sunday, I don‘t believe it would have been very difficult to have found out the names of the four or five youngsters I saw riding across to Groton. And if the combined efforts of the police court , the boys‘ parents and the railroad company didn‘t succeed in putting the fear of the Lord in the hearts of those boys so ss to make them seek some other sort of diversion thereafter, it would be a strange state of affairs. But nobody seems to mind. I even saw little girls six or seven years old climbing on the cars of a freight train stalled at the Harrison Street trestle, waiting for the pusher to help it up the grade; and nobody even said boo to them.

a judge steps in…

Finally. in November of 1922, under pressure from special agents working for both the Central Vermont and the New Haven railroads, Judge Victor Prince held a public hearing at juvenile court, having summoned to appear 22 boys and 8 girls, charged with stealing coal tossed from halted freight trains during the early morning hours. Over 50 other children came to eavesdrop, standing in the stairwell and hallway. The judge let it be known that he would start holding patents responsible for the actions of their children when it came to trespass and theft. He also expressed both the railroads‘ and the court‘s concern for the safety of the children. Judge Prince reminded the children that more than one or two unfortunate harvesters and surfers had lost a limb.

The practice of harvesting coal and surfing the boxcars diminished with the promised fines and support from the schools and youth clubs.

Courtesy The Day, 11/22/1922.

John Street

Union Station

Thames River drawbridge

State Pier

a man with a plan…

Employee morale was sinking as revenue sources pulled up stakes and went elsewhere or went non-rail. The friendly New Haven Railroad was getting a bit less friendly with every equipment failure and service delay or cancelation. Facing income shortfalls from a shrinking industrial base, restrictive labor agreements, car, truck and air competition, management sought creative ways to counter a very sobering financial outlook.

Brash and strong-willed, New Haven president Patrick B. McGinnis made some controversial investments and cutbacks that ultimately cost the railroad more than they saved… diesel power over electric, light-weight rough ride passenger train sets, the labor intensive Clejan trailer on flatcar program, deferred track maintenance and just plain bad luck with weather related washouts plagued the brief two-year tenure of Mr. McGinnis.

One plan that promised a big impact on the New London community involved closing Union Station and relocating the station elsewhere. We are in the early spring of 1955.

The McGinnis strategy started with an announcement in early 1955 that the railroad was looking to relocate passenger services to either Groton or Waterford. This ploy served in getting New London officials to sit up and be more receptive to ths railroad‘s needs. A preliminary plan was discussed whereby a new station with parking for 200 cars would be built just north of the current location using both railroad and non-railroad properties that city officials would help the New Haven acquire. This plan also called for the elimination of John and Hallam Street crossings.

New Haven Railroad president Patrick B. McGinnis taking questions from reporters at a press conference in Pittsfield on January 6, 1955.

Courtesy The Berkshire Eagle

The Central Vermont rail/foot bridge. This was the interchange track between the CV and the New Haven. Winthrop, Harrison Streets lie on the other end. Gold Star bridge (I-95) crowns the northern horizon. Late at night, this gauntlet could prove risky.

UCONN Archives, Peterson Collection, circa 1960

Herein came the rub. The people living on the Winthrop Cove peninsula (known as Neckers) in East New London used the Central Vermont footbridge and the Hallam Street crossing in reaching Main Street and downtown. Sailors from the sub tender Fulton, #11, and the subs serviced alongside also used this route in seeking their R&R or the train and bus stations. Under more scrutiny than most because of his family‘s New Haven connections, Mayor Richard J. Duggan suggested the Neckers petition the Public Utilities Commission to keep Hallam Street open. Some residents also rejected the installation of automatic gates, warning lights and bells, telling the mayor and city council they wanted eyes on the tracks. Clarence Martin who briefly sold used cars and those with an eye on economy, had a lot where the Salvation Army house at 243-45 Main once stood, wrote a letter to The Day urging the crossing remain open. The fire department also voices concerns over direct waterfront access should an emergency arise.

The Day, March 29, 1955

The discussion about a new station free of grade-level crossings dragged on through spring and early summer and then fell silent. At summer‘s end Hurricane Diane dumped a lot of rain on the Northeast causing severe flooding and declared states of emergency. On January 16, 1956, Patrick McGinnis broke the silence and publicly stated that there‘d be no new stations due to the financial strain of the hurricane damaged track work and rolling stock.

Two days later he left the New Haven for the somewhat less-troubled Boston & Maine.

more from the view…

While days and nights in the Hallam Street crossing tower proved generally predictable, the small knots of human activity outside were anything but. Under the cover of darkness the Central Vermont footbridge was sometimes a gauntlet for the sailors, longshoremen, and Neckers who used it. Dollar muggings of easy marks stumbling home alone from downtown, scores to settle with shipmates, class warfare between sailors on the sub tender Fulton and those on the subs it serviced broke out. The bridge was also an escape route for joy-riders leaving their ride by the tower and escaping by foot to be lost in the housing cluster on the other side. A few of the tenders no doubt welcomed the distraction.

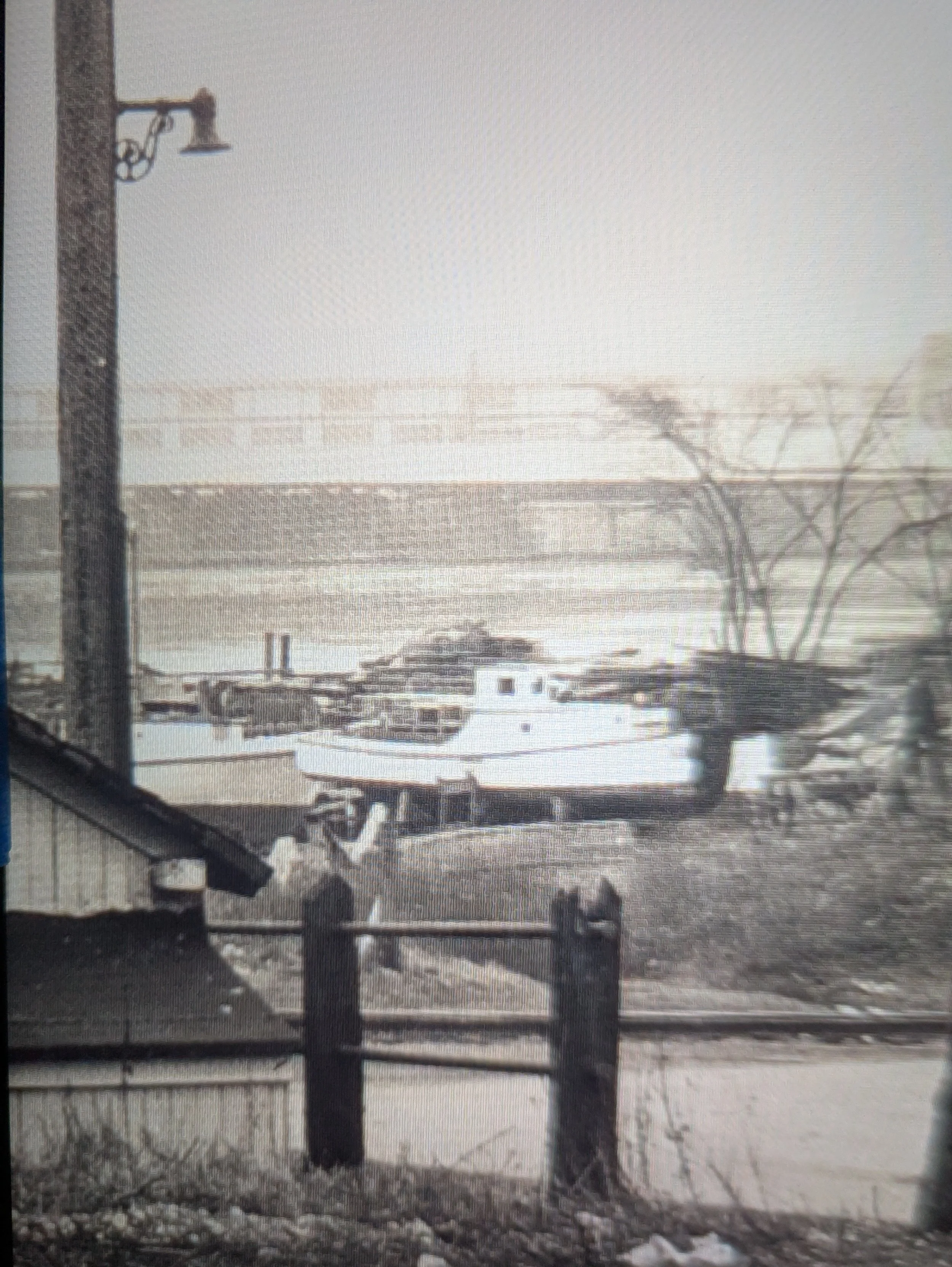

A small marina of lobster and fishing boats, the odd cabin cruiser found a relatively safe haven by the bridge from the weather only to be harassed from time to time by the equally unpredictable human element. No trespassing signs wire to the dock‘s chain link fence enclosure kept the curious at bay… but not always. On one occasion, a land pirate used a rock to enter the cabin of a 40‘ cruiser only to remain baffled by the motor controls. The expedition ended shortly thereafter where the owner found the boat adrift in shallow water near the far end of the bridge. The boat had been leaking and was listing to one side, scuttled by the pirate.

Opposite the marina on the other side of the bridge stood a blacksmith shop that first appeared on the Sanborn maps in 1901. John Femino or Jack, was the last tenant offering blacksmith and welding services, once in a while doing the quick odd job for the maintenance crew at the Hallam Street yard. Jack tried selling the New London Blacksmith in ˋ65, but there apparently were no takers. The following year, the shop was boarded up. Sailors connected with the Fulton would later squat the shop while car tinkering and beer drinking. Surprisingly, redevelopment did not take this property and it was only decades later the shop came down about the time of electrification by Amtrak.

the marina to the left in the foreground, the blacksmith shop on the far side of the interchange track, above the boat on the left

1961, George Oldershaw

the marina with a string of boxcars in the background along with the State Pier #1 Warehouse… left foreground is the blacksmith shop… note the street light fixture above. We are back in 1944.

UCONN Archives, Peterson Collection

This picture above, taken around 1963, shows the bow of the sub tender Fulton, #11, in the background. To the left is the marina and the New London Black Smith shop. Look at the candy striped crossing barriers. The extensions are simple unpainted 2x4s. Can you guess why?

On a Friday evening at 8:15, a car driving along Water Street went through these lowered barriers taking off a 3-foot section from each side. The car continued on to Main Street where it disappeared in traffic. Two days later, Robert Pearl, 24, of New London, turned himself in to the police in Kittery, Maine. Told to return to New London, the driver found himself in police court charged with evading responsibility and most likely received a fine.

The Day, 3/25/59

On another occasion, three sailors on their way back to the Experimental Destroyer Witek at the State Pier, decided in the early morning hours to have a playful game of battering ram with the descending barriers . As the gates lowered, the three took turns charging like bulls into the four barriers protecting the crossing. The tender reported the incident without intervening. All three were later discovered coated with white paint. The next morning the sailors were charged n police court with destruction of private property and, in addition to the court fine, were obliged to pay the railroad $35 in damages or remain in jail. Attorney C. Robert Satti was the prosecutor.

The Day, 2/26/58

Engine #1414 in a better light a year later at the New Haven engine terminal in 1965.

The New Haven Railroad Historical and Technical Association

the mystery of Engine #1414…

Early in the daylight hours of May 19, 1964, Alco RS-11 #1414 left the rails while performing light switching duties near the Hallam Street crossing. A local crew used another engine in getting #1414 back on the rails.

The cause? Unknown. At this point in time the words under investigation were enjoying a second wind. Interestingly, the New Haven management reported no damage to the engine or the track.

This engine was the last in a delivery of 16 RS-11 switchers to the railroad in the summer of ˋ56 and would later push/pull for the Penn Central as #7474 and for Conrail as #7599.

The Day, 5/19/64

thumbnails…

A sleeping sailor misses his stop in New London and wakes up just as the train is pulling out. Running back to the last car, he climbs over the railing and jumps just before the Hallam Street crossing. A track crew sees his rough landing, gives him first aid, and calls the police. After being treated at New London‘s Lawrence & Memorial Hospital for body bruises and a back injury, an ambulance takes him to the sub base hospital for further treatment. The sailor made muster after all, and it being St. Patrick‘s Day, had the luck of the Irish. The Day, 3/17/58

Luck smiled as well on a young woman brushed by a train six years later. Barbara Fox of Winthrop Street was headed home at night in the pouring rain. While using the crossing she heard a loud horn as if on top of her. It was. A Boston-bound passenger train roared by hitting her elbow, sending her flying 10 feet onto the street. The engineer put his train into emergency stop, climbed down from the cab and ran back to the crossing. Just a sore left arm and ankle, nothing more, she said. After a brief rest, Mrs. Fox continued her walk home and the engineer proceeded to take his train to Boston . The Day, 11/20/64

We were lucky, I guess… railroad spokesman, unnamed

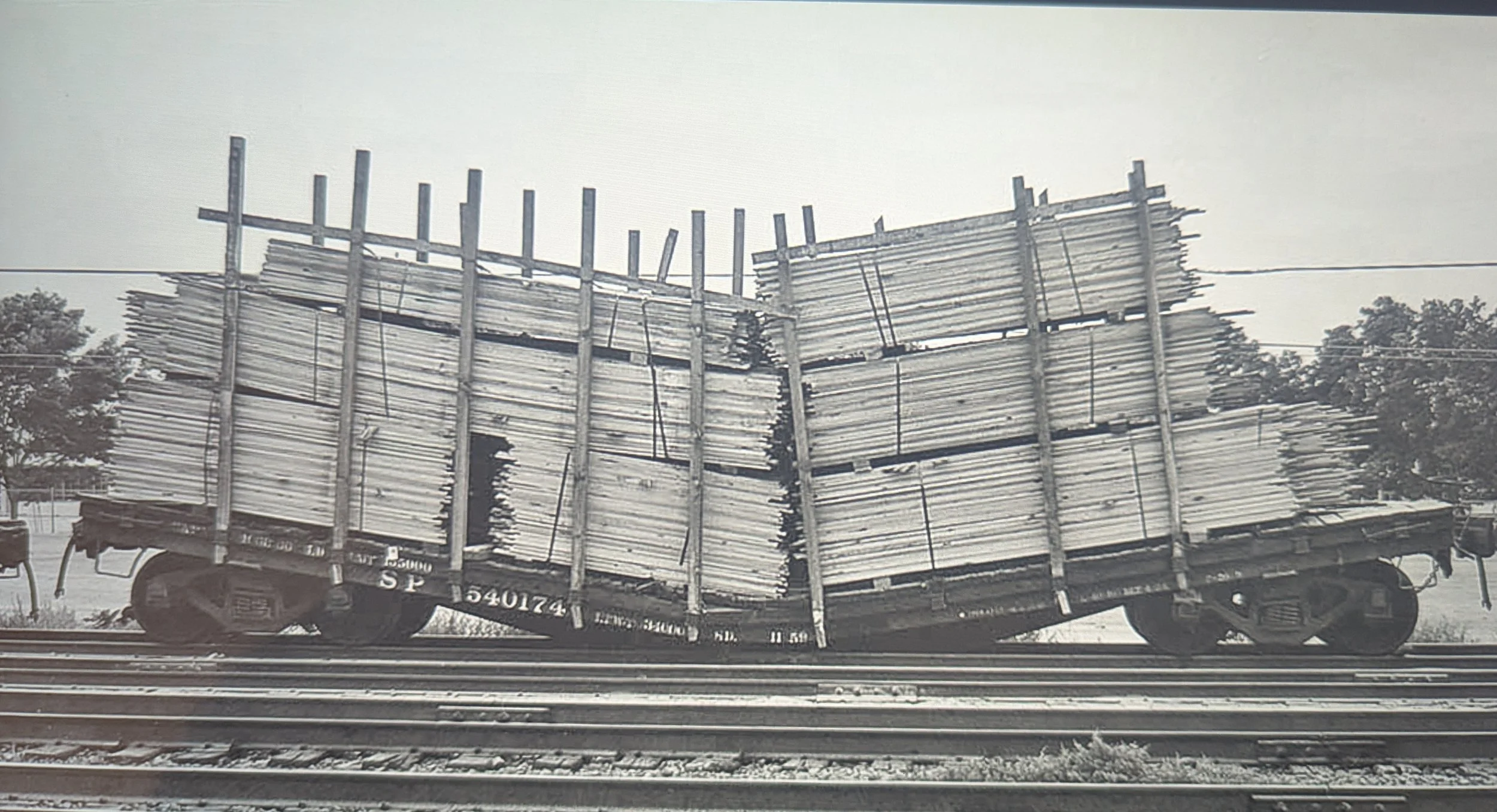

During the early morning hours as a 67-car freight snaked its way through New London to the classification yard at Cedar Hill in New Haven, a flatcar, heavily laden with lumber, buckled as it rolled over Hallam Street. The car sank in the middle nearly making contact with the rails underneath. At the John and City Pier (Union Station) crossings the car acted as a carpenter‘s plane, shaving asphalt and ties between the rails. The train finally came to a halt half a mile later. Though crippled, the flatcar remained in one piece and still on the track.

Dispatch sent a wreck train from New Haven while the stricken train‘s crew picked up the cars fore and aft of the broken flat and continued on to Cedar Hill, 66 cars and a caboose in tow. The wreck crew unloaded the stranded flat and carried it piggy back to New Haven. The men also regraded the two damaged crossings , respiked some of the rail and replaced several ties. No injuries to report, no derailments to clean up or explain. On May 23, 1967, the luck of the Irish continued to hold for the New Haven Railroad.

The Day, 5/23/67

the New Haven was by no means unique in the car failure department…

from the photograph collection of Elmer K Hall

to be continued…